12 R and Your Computer

“Those who can imagine anything, can create the impossible.”

- Alan Turing, (1912–1954)

12.1 What is a Computer?

To better understand R, we need to understand the underlying characteristics and constraints of computer systems we use to run R. Computers accept data, process data, produce output, and store processed results. This is generally accomplished through through the generation, integration, and storage of electrical signals at microscopic scales. A computer is comprised of two basic components.

-

Hardware refers to the actual physical parts computer including processors, discs and the power supply.

- Software refers to computer programs that allow a computer to run and perform specific tasks. Software can be subset into two components: operating systems and applications. R is an example of application software.

12.1.1 Operating Systems and Processor Architectures

An operating system (OS) is “the layer of software that manages a computer’s resources for its users and their applications” (T. Anderson and Dahlin 2014). Operating systems include permanently running kernel software –that always have complete control over the computer– and other software, including system programs like command line interfaces, file managers, compilers and debuggers.

There are currently three major desktop/laptop operating systems. From most-to-least popular these are: Windows (71% market share), Mac-OS (16%), and Linux (4%) (Wikipedia 2025w). Although R can be run on all three platforms, designing cross-platform R packages (Chapter 10) can be challenging, particularly if those packages generate GUIs (Chapter 11). Both Mac-OS and Linux are considered “Unix-like”, meaning that they behave similarly to a Unix system (Wikipedia 2025v). These similarities include the incorporation of particular shell frameworks (e.g., BASH; Section 9.2) and Unix commands. Like Unix, current Mac-OS computers are considered POSIX compliant, although not all versions of Linux meet this criterion (Wikipedia 2025o). Nonetheless, Dennis Ritchie –who with Ken Thompson created Unix and the C language– has argued that Linux is a particularly strong adherent to original Unix programming principles (Benet 1999). Windows, Mac and Unix, are proprietary operating systems, whereas Linux is open source, and allows a great deal of user-freedom in managing software.

R can currently run on Mac computers with Advanced RISC Machine (ARM) 64-bit (see Section 12.6) Central Processing Units (CPUs), and Linux, Windows, and Mac computers with x86 64-bit CPUs. ARM processors are relatively inexpensive, and optimize power efficiency over analytical power (Wikipedia 2025b). Thus, ARM processors are often used in mobile devices and laptops to increase battery life. On the other hand, x86 processors emphasize computing performance over power efficiency, and are frequently used in desktop computers and servers.

Information about your computer’s operating system and processor architecture can be obtained with the function Sys.info()

Sys.info()[1:5] sysname release version nodename machine

"Windows" "10 x64" "build 26100" "AHOKENC02549" "x86-64"

12.1.2 Computer Components

A list of (current but often changing) computer hardware terms are given below.

-

Central Processing Unit (CPU): A microprocessor (generally x86 or ARM) that performs most of the calculations that allow a computer to function. The CPU processes program instructions and sends the results on for further processing and execution by other computer components. A modern CPU generally consists of 4-8 cores built onto a single chip. Each CPU core will generally contain (Fig 12.1):

- A Register that allows rapid access to data, primary memory addresses, and machine code instructions. Modern x86 processors often have multiple architectural registers to improve computational performance through parallel execution.

- A Control Unit (CU) to direct the flow of data between the CPU and the other devices.

- An Arithmetic and Logical Unit to perform bitwise (Section 12.3) operations on integer binary numbers.

-

You can check the number151 of available CPU cores on your computer by running:

parallel::detectCores()[1] 6

FIGURE 12.1: Block computer hardware archtecture, emaphasing the CPU. Black lines show the flow of control signals, and orange lines indicate the flow of processor instructions and data. Figure follows: Amila Ruwan 20 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95966225

- Graphics Processing Unit (GPU): An electronic circuit originally designed to accelerate computer graphics, but now widely applied for non-graphic, but highly parallel, calculations. The GPU allows the CPU to run concurrent processes. A GPU can have hundreds or thousands of cores. A number of R packages have been designed to utilize GPUs instead of CPUs to increase computational efficiency.

-

The presence of Windows GPUs can be detected using PowerShell.

Name

----

Intel(R) UHD Graphics 630-

The Intel\(^{\circledR}\) UHD Graphics 630 is a popular integrated GPU.

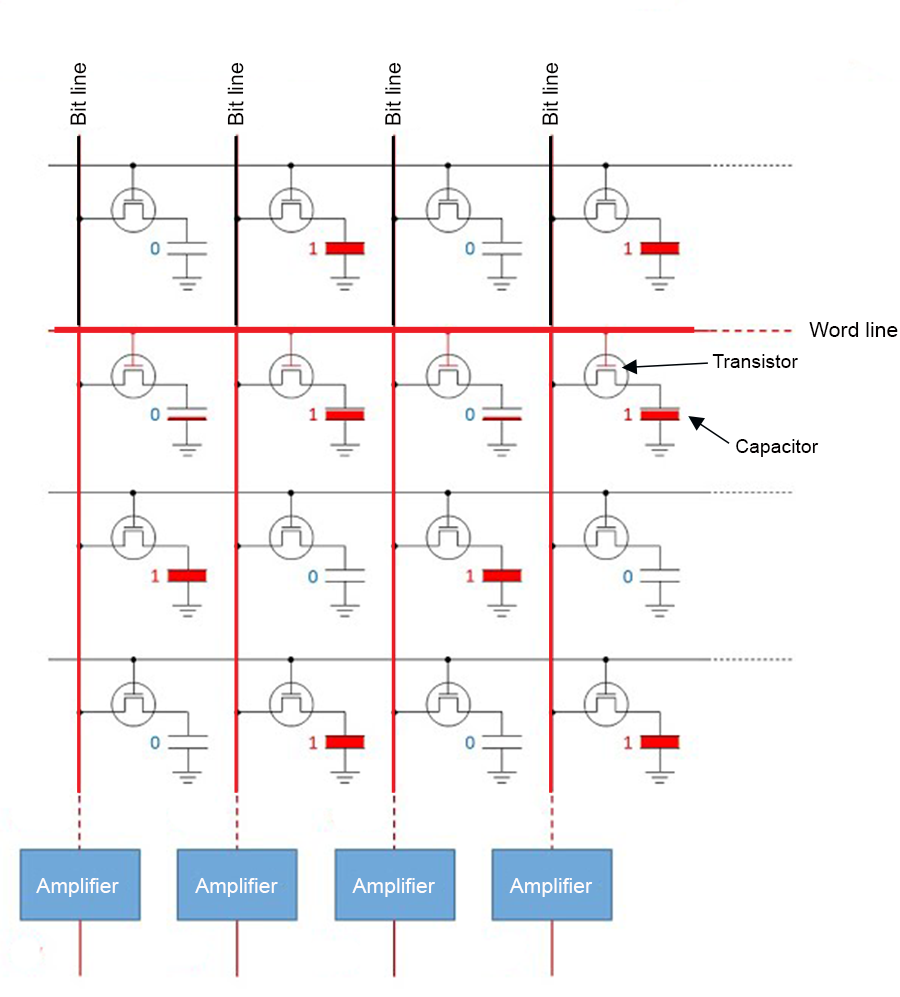

- Random Access Memory (RAM): Stores code and data in primary memory to allow it to be directly accessed by the CPU (Fig 12.1). RAM is volatile memory which requires power to retain stored information. Thus, when power is interrupted, RAM data can be lost. RAM types include dynamic random access memory (DRAM) and static random-access memory (SRAM). DRAM constitutes modern computer main memory and graphics cards. DRAM typically takes the form of an integrated circuit chip that can consist of up to billions of memory cells, with each cell consisting of a pairing of a tiny capacitor152 and transistor153, allowing each cell to store or read or write one bit of information (Fig 12.2). SRAM uses latching circuitry that holds data permanently in the presence of power, whereas DRAM decays in seconds and must be periodically refreshed. Memory access via SRAM is much faster than DRAM, although DRAM circuits are much less expensive to construct.

FIGURE 12.2: Sixteen DRAM memory cells each representing a bit of information for computational storage, reading, or writing. To read the binary word line 0101... in row two of the circuit, binary signals are sent down the bit lines to sense amplifiers.

Read-Only Memory (ROM): Primary memory (Fig 12.1) for software that is rarely changed (i.e. firmware). Includes functions for initializing hardware components and loading the operating system.

Motherboard: A circuit board physically connecting computer components including the CPU, RAM, ROM, and memory disk drives.

Disk drives: including CD, DVD, hard disk (HDD), and solid state disk (SSD) are used for secondary memory. That is, memory that is not directly accessible from the CPU. Secondary memory can be accessed or retrieved even if the computer is off. Secondary memory is also non-volatile and thus can be used to store data and programs for extended periods. User files and application software (like R) are generally stored on HDDs or SSDs. Flash memory, which uses modified metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs), is typically used on USB and SSD devices to provide secondary memory that can be erased and reprogrammed. Flash memory can also be used in RAM applications.

Basic Input Output System (BIOS): Basic boot (startup) and power management firmware (software that provides low level control for computer hardware). Although historically, BIOS was stored on a physical ROM chip. It is now stored on a flash memory chip that can be updated.

Video card: Processes computer graphics.

12.2 Base-2 and Base-10

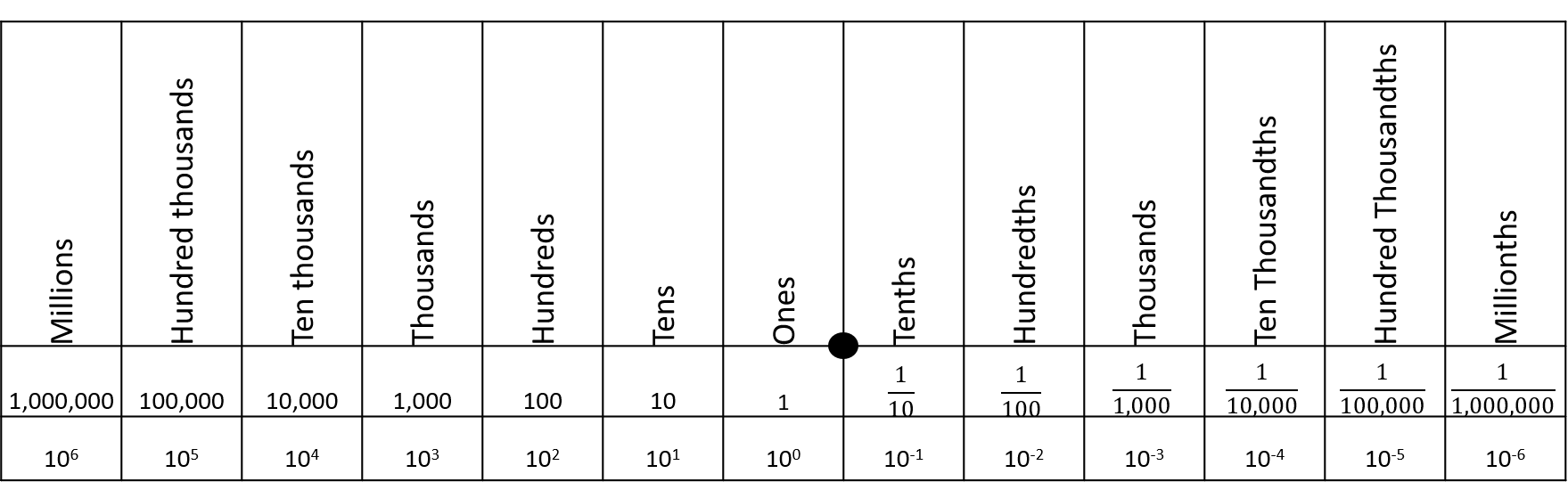

To understand computer processes, it is important to distinguish base-2 (binary) and base-10 (decimal) numerical systems. In both cases, the base refers to the number of unique digits. Thus, base-2 systems can have two unique digits, commonly \(0\) and \(1\), and the base-10 system has 10 unique digits: \(0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\). The latter –more widely used system– probably arose because we have ten fingers for counting154. A radix (commonly a decimal symbol) is used to distinguish the integer part of a number from its fractional part (Fig 12.3). The radix convention is used by both base-2 and base-10 systems. For example, the decimal number \(4\frac{3}{4}\), has integer component \(4\) and fractional component \(\frac{3}{4}\), and can be expressed as \(4.75\). The binary equivalent of \(4\frac{3}{4}\) is 100.110.

Traditionally, a base-10 number could only be expressed as a rational fraction whose denominator was a power of ten (Fig 12.3). However, the decimal system can be extended to any real number, by allowing a conceptual infinite sequence of digits following the radix (Wikipedia 2025g).

FIGURE 12.3: A decimal place value chart. A radix (decimal) is placed between the ones and thenths columns to distinguish decimal number components greater than one (to the left), and components less than one but greater than zero (to the right).

12.3 Bits and Bytes

Computers are designed around bits and bytes. A bit is a binary (base-2) unit of digital information. Specifically, a bit will represent a 0 or a 1. This convention occurs because computer systems typically use electronic circuits that exist in only one of two states, on or off. For instance, DRAM memory cells (Fig 12.2) convert electrical low and high voltages into binary 0 and 1 responses, respectively. These signals allow the reading, writing, and storage of data. Although bits are used by all software in all conventional computer operating systems, these mechanisms are easily revealed in R.

For historical reasons, bits are generally counted in units of bytes. A byte equals eight bits. There are two major systems for counting bytes. The most common uses powers of 10, allowing implementation of SI prefixes (i.e., kilo = \(10^3 = 1000\), mega = \(10^6\) = \(1000^2\), giga = \(10^9\) = \(1000^3\), etc.) (Table 12.1). A computer hard drive with 1 gigabyte (1 billion bytes) of memory will have \(1 \times 10^9\) bytes = \(8 \times 10^9\) bits of memory. A second system, used frequently by Windows to describe RAM, uses a base-2 approach, with the conventions: \(2^{10} = 1024\) = kibi, \(2^{20} = 1024^2\) = mebi, \(2^{20} = 1024^2\) = gibi, etc. (Table 12.1).

| Base-10 | Base-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bytes | Name | Bytes | Name (IEC) |

| \(1000\) | kB (kilobyte) | \(1024\) | KiB (kibibyte) |

| \(1000^2\) | MB (megabyte) | \(1024^2\) | MiB (mebibyte) |

| \(1000^3\) | GB (gigabyte) | \(1024^3\) | GiB (gibibyte) |

| \(1000^4\) | TB (terabyte) | \(1024^4\) | TiB (tebibyte) |

| \(1000^5\) | PB (petabyte) | \(1024^5\) | PeB (pebibyte) |

With a single bit we can describe only \(2^1 = 2\) distinct digital objects. These will be an entity represented by a 0, and an entity represented by a 1. It follows that \(2^2 = 4\) distinct objects can be described with two bits, \(2^3 = 8\) entities can be described with three bits, and so on155.

Example 12.1 \(\text{}\)

One can get the total RAM on a Windows machine using PowerShell

31.8010673522949I have around 32 gigabytes of RAM.

\(\blacksquare\)

12.4 Decimal to Binary

We count to ten in binary using: 0 = 0, 1 = 1, 10 = 2, 11 = 3, 100 = 4, 101 = 5, 110 = 6, 111 = 7, 1000 = 8, 1001 = 9, and 1010 = 10. Thus, we require four bits to count to ten. Note that the binary sequences for all positive integers greater than or equal to one, start with one.

12.4.1 Positive Integers

We can obtain the binary expression of the integer part of any decimal number by iteratively performing integer division by two, and cataloging each modulus. The iterations are stopped when a quotient of one is reached. The modulus sequence is read from right to left (backwards). If the whole number of interest is greater than one (i.e., the whole number is not 0 or 1) we place a one in front of the reversed sequence, because all binary sequences for numbers greater than or equal to one must start with one.

Example 12.2 \(\text{}\)

Consider the number 23:

\[ \begin{aligned} &\text{Modulus (remainder) }& 1& & 1& & 1& & 0&\\ &\text{Integer Quotient } & 23/2 = 11& & 11/2 = 5& & 5/2 = 2& & 2/2 = 1& \end{aligned} \]

The reversed sequence is 0111. We place a one in front to get the binary representation for 23: 10111. The function dec2bin() from asbio does the work for us:

[1] 10111\(\blacksquare\)

12.4.2 Positive Fractions

The fractional part of a decimal number can be converted to binary in a similar fashion.

- To identify the fractional expression as a non integer, start the binary sequence with

0.(a zero followed by a decimal symbol). - Double the fraction to be converted, and record a

1if the product is \(\ge 1\), and0otherwise. - For subsequent binary digits, multiply two by the fractional part of the previous multiplication. If the product is \(\ge 1\), record a

1. If not, record a0.

Example 12.3 \(\text{}\)

Consider the fraction \(\frac{1}{4}\). We have:

\[ \begin{aligned} &\text{Binary outcome}& 0 && 1\\ &\text{Product} & 1/4 \times 2 = 1/2 < 1 && 1/2 \times 2 = 1\ge 1 \\ &\text{Binary outcome}& 0 && 0\\ &\text{Product} & 0 \times 2 = 0 < 1 && 0 \times 2 = 0 < 1 \end{aligned} \]

\(\blacksquare\)

We have a clear repeating sequence of zeroes, due to a product of two in the second step. This allows us to stop the growth of the binary expression. For fractions, the binary sequence is read conventionally, from left to right. Thus, the binary expression for \(\frac{1}{4}\) is 0.01 .

dec2bin(0.25)[1] 0.0112.5 Binary to Decimal

Numeric outcomes from an underling base framework (e.g., binary or decimal) can be considered as a dot product (the sum of the element-wise multiplication of two numeric vectors). This can be defined using an equation based on Horner’s method (Horner 1815).

\[\begin{equation} \sum_{\kappa=\min(\kappa)}^{\max(\kappa)}\alpha\beta^\kappa \tag{12.1} \end{equation}\]

Here \(\alpha\) is a quantity known as the significand, which contains individual numeric outcomes (0-9 in decimal, or 0 or 1 in binary) outcomes. \(\beta\) is the the modifying base, For the purpose of binary expressions, \(\beta\), is 2, whereas for decimal expressions, it is 10. The term \(\kappa\) is called (appropriately) the exponent. The maximum and minimum values of \(\kappa\) are determined by counting the number of placeholder digits in the expression represented by the significand, with respect to a radix point (Fig 12.4). Note that counting starts with respect to 0 (the first digit to the left of the radix) for both positive (terms to the left of the radix) and negative (terms to the right of the radix) values of the exponent, \(\kappa\). The radix reference has prompted this method to be called floating point arithmetic.

Example 12.4 \(\text{}\)

This concept is easy to demonstrate with a conventional decimal (base 10) number. Consider the number \(1,245.42\). We have:

\[ \begin{aligned} &1 \times 10^3 + 2 \times 10^2 + 4 \times 10^1 + 5 \times 10^0 + 4 \times 10^{-1} + 2 \times 10^{-2}= \\ &1000 \hspace{.22in}+ 200 \hspace{.315in}+ 40 \hspace{.42in}+ 5 \hspace{.51in}+ 0.4 \hspace{.465in}+ 0.02 \hspace{.36in}= 1245.42 \end{aligned} \]

\(\blacksquare\)

12.5.1 Positive Integers

The addition of a binary digit (i.e., a bit) represents a doubling of information storage. For instance, as we increase from two bits to three bits, the number of describable integers increases from four (integers 0 to 3) to eight (integers 0 to 7). As a result we say that the rightmost digit in a set of binary digits represents \(2^0\), the next represents \(2^1\), then \(2^2\), in Eq (12.1) and so on.

For positive integers the entirety of a corresponding binary expression will be to the left of the radix point (Fig 12.4). Thus, the minimum value of \(\kappa\) will be zero and the maximum value of \(\kappa\) will be the number of digits (bits) in the binary expression, minus one. When applying Equation (12.1) to find the integers represented by a single binary bit, we multiply the binary digit value, 0 or 1, by the power of two it represents. Because the single bit signature would occur at the right-most address to the left of the radix, the value of exponent would be 0 (Fig 12.4). That is, \(\min(\kappa)\) = \(\max(\kappa)\) = 0 in Eq. (12.1).

If a single bit equals 0 we have:

\[0 \times 2^0 = 0,\]

and if the single bit equals 1 we have:

\[1 \times 2^0 = 1.\]

Accordingly, to find the decimal version of a set of binary values, we take the sum of the products of the binary digits and their corresponding (decreasing) powers of base 2.

FIGURE 12.4: Conceptualization of binary to decimal conversion of a positive integer and positive fraction, as given in Eq (12.1).

Example 12.5 \(\text{}\)

For example, the binary number 010101 equals:

\[ \begin{aligned} &(0 \times 2^5) + (1 \times 2^4) + \\ &(0 \times 2^3) + (1 \times 2^2) + \\ &(0 \times 2^1) + (1 \times 2^0) = \\ &0 + 16 + 0 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 21.\\ \end{aligned} \]

The function bin2dec in asbio does the calculation for us.

bin2dec(010101)[1] 21\(\blacksquare\)

12.5.2 Positive Fractions

For positive fractions, values of the \(\kappa\) exponent will decrease by minus one as bits increase by one (Fig 12.4). Thus, to obtain decimal fractions from binary fractions we multiply a bit’s binary value by decreasing negative powers of base two, starting at 0, and find the sum, as shown in Eq (12.1).

Example 12.6 \(\text{}\)

For example, the binary value 0.01 equals:

\[(0 \times 2^0) + (0 \times 2^{-1}) + (1 \times 2^{-2}) = 0.25\]

bin2dec(0.01)[1] 0.25\(\blacksquare\)

12.5.2.1 Terminality

Most decimal fractions will not have a clear terminal binary sequence. That is, a binary representation of a decimal fraction with a finite number of digits will not exist. This results in mere binary approximations of decimal numbers (Goldberg 1991). For instance, the 10 bit binary expression of \(\frac{1}{10}\) is

dec2bin(0.1)[1] 0.0001100110But translating this back to decimal we find:

bin2dec(0.0001100110)[1] 0.0996We can increase the number of bits in the binary expression,

dec2bin(0.1, max.bits = 14)[1] 0.00011001100110This increases precision, but the decimal approximation remains imperfect.

[1] 0.10000000000000000555

1/10[1] 0.10000000000000000555Note that these imperfect conversions are the actual results of the division \(\frac{1}{10}\) for all software on all current conventional computers (not just R)!

It may seem surprising that rational fractions like \(\frac{1}{10}\) may have non-terminating binary expressions. Terminality, however, will only occur for a decimal fraction if a product of 2 results from the successive multiplication steps described in Section 12.4.2. This product does not occur for \(\frac{1}{10}\).

Lack of terminality for binary expressions prompts the need for quantifying imprecision in computers systems. This can be obtained from Eq (12.1). In particular, the exponent in Eq (12.1) determines minimum and maximum possible encoded numeric values, and the number of digits in the significand determines numeric precision. Indeed, by changing the base from 2 to 10, Eq (12.1) can be used to quantify the precision of binary and decimal numbers.

The decimal number \(1,245.42\) has the scientific notation: \(1.24542 \times 10^3\). The expression has a the precision of six digits, because under Eq (12.1) the significand has six digits.

12.6 Double Precision

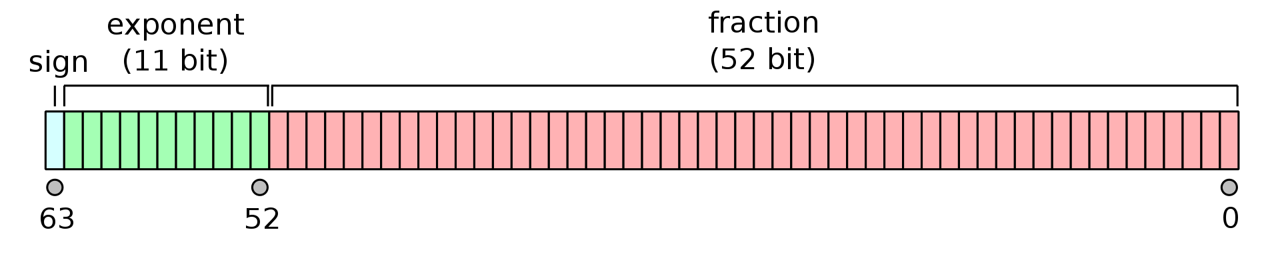

In most programs, on most workstations, the results of computations are stored as 32 bits (i.e., 4 bytes) or as 64 bits (8 bytes) of information. The 64 bit double precision format allows high precision representations of both positive and negative integers and their fractional components. Under this framework, one bit is allocated to the sign of the stored item, 53 bits are assigned to the significand, and 11 bits are given to the exponent (Fig 12.5).

FIGURE 12.5: The IEEE 754 double-precision binary floating-point format. Figure follows (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3595583).

This can be represented mathematically as a more complex form of Eq (12.1):

\[\begin{equation} (-1)^{\text{sign}}\left(1 + \sum_{i=1}^{52} b_{52-i} 2^{-i} \right)\times 2^{e-1023} \tag{12.2} \end{equation}\]

which gives the assumed numeric value for a 64-bit double-precision datum with exponent bias. The term sign refers to the first (sign) bit, \(e\) refers to the numeric translation of the 11 bit exponent (it does not represent Euler’s constant), and \(b\) refers to other 52 indexed bits in the significand (Fig 12.5).

Example 12.7 \(\text{}\)

The function bit64() below is taken from the Examples of the documentation for the base function numToBits(), which converts digital numbers to 64 bits using packets of two binary digits (the second of which can be used in 64 bit expressions). The function distinguishes:

- The single bit giving the sign of the number (

0= positive,1= negative). - The 11 bit exponent.

- A 52 bit significand (without the implicit leading

1).

bit64 <- function(x)

noquote(vapply(as.double(x),

function(x) {

b <- substr(

as.character(rev(numToBits(x))), 2L, 2L)

paste0(c(b[1L], " ", b[2:12], " | ", b[13:64]),

collapse = "")}, "")

)- On Line 2, the script

noquote(vapply(as.double(x),initiates the functionvapply()which will return a vector of results given the application of some function (specified as the second argument invapply()) to some object (defined in the first argument ofvapply()). The first argument ofvapply()here is a double precision object coerced from the sole argument,xrequired bybit64(). The ultimate output frombit64()is a character string. The functionnoquote()will remove quotes from the string when the results are printed. - Lines 3-6 define the function to be run by

vapply()in it its second argument. That is, these lines are contained in the call tovapply().- The script on Line 4:

substr(as.character(rev(numToBits(x))), 2L, 2L)obtains 64 packets, each comprised of two memory bits, representing the decimal number inx, usingnumToBits(x), then reverses those packets withrev(), then converts those packets to strings withas.character()and finally retrieves the second digits from each packet withsubstr(., 2L, 2L). - On Lines 5-6 the character vector of length 64,

b, resulting from processes in Line 4, is subset into the sign bitb[1L], the exponentb[2:12], and the significandb[13:64]components of the 64 bit representation.

- The script on Line 4:

Here is the double precision representation of \(\frac{1}{3}\)

bit64(1/3)[1] 0 01111111101 | 0101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101We see this follows the form of Eq (12.2). The exponent 01111111101 represents the decimal number 1021:

bin2dec(01111111101)[1] 1021And one plus the dot product of the significand and base-2 raised to the sequence -1 to -52, multiplied by \(2^{1021 - 1023}\), is:

sigd <- strsplit(

"0101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101", NULL)

sigd <- as.numeric(unlist(sigd))

base2 <- 2^(-1:-52)

(1 + sum(sigd * base2)) * 2^-2[1] 0.3333333That is, we have:

\[ \begin{aligned} value &= (-1)^{\text{sign}}\left(1 + \sum_{i=1}^{52} b_{52-i} 2^{-i} \right)\times 2^{e-1023}\\ &= -1^{0} \times (1 + 2^{-2} + 2^{-4} + \dots + 2^{-52}) \times 2^{1021-1023}\\ &\approx 1.33\bar{3} \times 2^{-2}\\ &\approx \frac{1}{3} \end{aligned} \]

\(\blacksquare\)

The 11 bit width of the double precision exponent allows the expression of numbers between \(10^{-308}\) and \(10^{308}\), with full 15–17 decimal digits precision. This is clearly demonstrated in R. Specifically, imprecision problems with non-terminal fractions become evident for decimal numbers with greater than 16 displayed digital digits.

options(digits = 18)

1/3[1] 0.333333333333333315Additionally, the current upper numerical limit in R (ver 4.3.2) is somewhere between:

1.8 * 10^307[1] 1.8e+307and

1.8 * 10^308[1] InfThe so-called subnormal representation156 compromises precision, but allows allows fractional representations approaching \(5 \times 10^{-324}\). This approach is used by R, whose smallest represented fraction is between:

5.0 * 10^-323[1] 4.94065645841246544e-323and

5.0 * 10^-324[1] 0Binary fractional numbers are expressed with respect to a decimal, and the number of digits will (often) be dictated by the significand. Given 13 bits we have the following binary translations to decimal numbers: 1 = 1/1, 0.1 = 1/2, = 1/3, 0.01 = 1/4, 0.00110011 = 1/5, = 1/6, = 1/7, 0.001 = 1/8, = 1/9, = 1/10.

12.7 Hexadecimal

After base 2, hexadecimal (base 16) is the most common numerical system used in computing (Haddock and Dunn 2011). The system uses the hexes A-F or a-f to represent decimal numbers 10-15. Thus, in order, the sixteen unique hexes are: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F. To indicate that the hexadecimal system is being used by a computer, hex values are often written with a preceding 0 or 0x. Thus, 0F, 0xF could be used to represent the hex A, the 16th hex, which corresponds to decimal number 15, and the binary representation 1111. Subscripts are often used to distinguish decimal, binary and hexadecimal representations. For instance, 1510 = 11112 = F16. One would reuse hexes for numbers larger than 15, just as one would reuse decimal digits to represent numbers larger than 9. For instance,

1016 = 1610, 2016 = 3210, 3016 = 4810, \(\dots\), A016 = 16010, and so on.

Example 12.8 \(\text{}\)

Here I use asbio::dec2bin() and base::as.hexmode() to obtain binary and hexadecimal representations of the first twenty-one decimal numbers, including zero.

dec <- 0:20

bin <- sapply(dec, dec2bin)

hex <- format(as.hexmode(dec))

data.frame(Decimal = dec, Binary = bin, Hexadecimal = hex) Decimal Binary Hexadecimal

1 0 0 00

2 1 1 01

3 2 10 02

4 3 11 03

5 4 100 04

6 5 101 05

7 6 110 06

8 7 111 07

9 8 1000 08

10 9 1001 09

11 10 1010 0a

12 11 1011 0b

13 12 1100 0c

14 13 1101 0d

15 14 1110 0e

16 15 1111 0f

17 16 10000 10

18 17 10001 11

19 18 10010 12

20 19 10011 13

21 20 10100 14\(\blacksquare\)

An advantage of hexadecimal is that it allows simpler and more readable representations than binary. This is because the eight bits from one byte will correspond to exactly two hex digits.

12.8 Binary and Hexadecimal Characters

Characters can also be expressed in binary or hexadecimal. The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) encoding system consists of 128 characters, and requires one byte = eight bits157. The newer eight bit Unicode Transformation Format (UTF-8) system –the one used by R– can represent 1,112,064 valid code points, using between 1 to 4 bytes (= 8 to 32 bits) (Wikipedia 2025y), although currently only 297,334 have actually been assigned to characters. Specifically, from the perspective of the UTF-16 system, the UTF-8 system uses portions of seventeen planes 158, each consisting of sixteen bits (and, thus, \(2^{16} = 65,536\) code variants). This results in the quantity:

\[(17 \times 2^{16}) - 2^{11} = 1,112,064\]

The \(2^{11} = 2048\) subtraction acknowledges that there are 2048 technically-invalid Unicode surrogates (Wikipedia 2025x). The first 128 UTF-8 characters are the ASCII characters, allowing back-comparability with ASCII.

Example 12.9 \(\text{}\)

We can observe the process of binary character assignment in R using the functions as.raw(), rawToChar(), and rawToBits(). The base type raw (Section 2.3.7) is intended to hold raw byte information. Here is a list of the 128 ASCII characters.

[1] "\001" "\002" "\003" "\004" "\005" "\006" "\a" "\b" "\t" "\n"

[11] "\v" "\f" "\r" "\016" "\017" "\020" "\021" "\022" "\023" "\024"

[21] "\025" "\026" "\027" "\030" "\031" "\032" "\033" "\034" "\035" "\036"

[31] "\037" " " "!" "\"" "#" "$" "%" "&" "'" "("

[41] ")" "*" "+" "," "-" "." "/" "0" "1" "2"

[51] "3" "4" "5" "6" "7" "8" "9" ":" ";" "<"

[61] "=" ">" "?" "@" "A" "B" "C" "D" "E" "F"

[71] "G" "H" "I" "J" "K" "L" "M" "N" "O" "P"

[81] "Q" "R" "S" "T" "U" "V" "W" "X" "Y" "Z"

[91] "[" "\\" "]" "^" "_" "`" "a" "b" "c" "d"

[101] "e" "f" "g" "h" "i" "j" "k" "l" "m" "n"

[111] "o" "p" "q" "r" "s" "t" "u" "v" "w" "x"

[121] "y" "z" "{" "|" "}" "~" "\177" "\x80"Note that the exclamation point is character number 33. Its 16 bit binary code is:

[1] 01 00 00 00 00 01 00 00From the output above, codes 1-31 and 127-128 are non-printable control characters. For instance, recall (Section 4.3.3.4) that \t (ASCII code 9) represents the tab key, Tab, and \n (ASCII code 10) represents new line. Thus, there are only 128 - 33 = 95 printable ASCII characters.

\(\blacksquare\)

Hexadecimal representations are usually used to denote Unicode characters by preceding the hex number with 0x00. The prefix \u00, however, is generally used in R159.

Example 12.10 \(\text{}\)

For instance, the explanation point $ is the 36th Unicode (and ASCII) character (Example 12.9). The 36th hex number (the hex representation of 3510) is 2416. So, the hexadecimal representation of $ is 0x0024. This can be verified with the base function intToUtf8().

intToUtf8("0x0024")[1] "$"We could use "\u0024" to obtain the Unicode character $ without using intToUtf8().

"\u0024"[1] "$"\(\blacksquare\)

12.9 R, the Internet and the Web

For many R tasks, including administration of Shiny apps (Section 11.5.7.2) and data import from webpages (see Examples in Section 12.9.2), it will be useful to have a basic understanding the workings of the internet and the world wide web.

12.9.1 The Internet

Under the idiom of computer science, a network is a group of computers. A local area network (LAN) connects devices (computers, printers, etc.) within a specific area (a residence, building, etc.) to each other. Connections between networks components are can be maintained thorough a combination of Ethernet cables, fiber-optic cables, and radio wave signals.

The internet is a global collection of networks, continually communicating with one another, via packets of information made up of digital bits, through a series of formal procedures160.

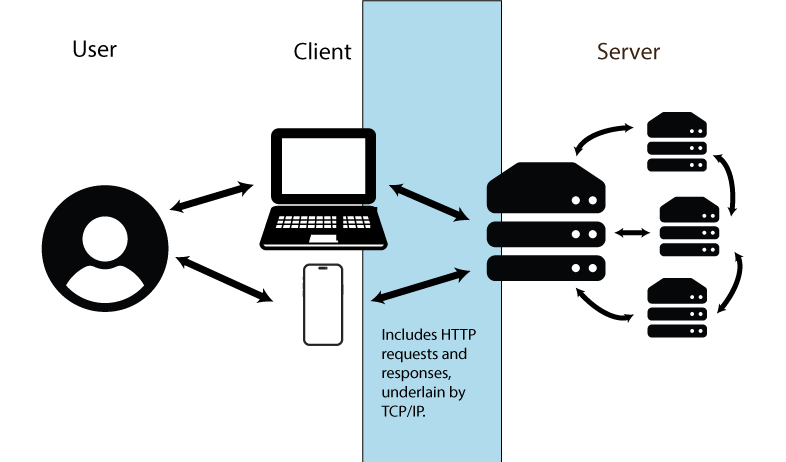

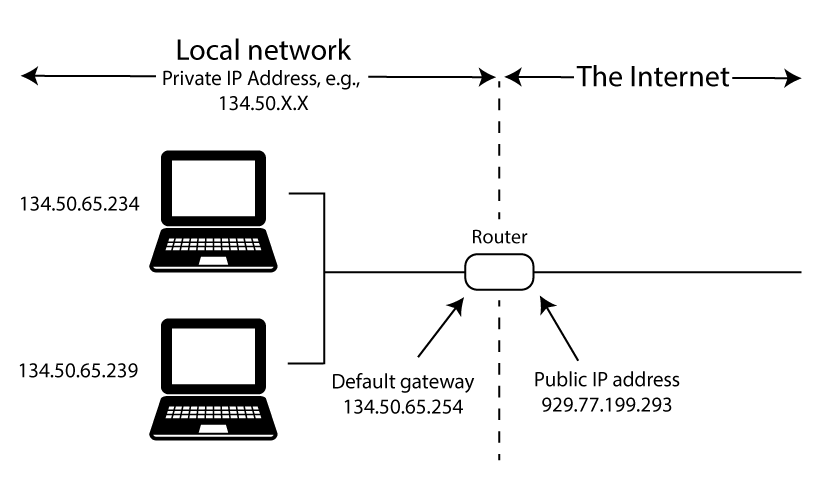

Internet information exchanges can be simplified into three components (Figure 12.6).

- The User is the person accessing/using the internet.

- The Client is a device (e.g., workstation, laptop tablet, phone) employed by the user to transfer information to and from remote servers.

- The Server is a continuously running computer or network of computers that handles tasks including website hosting, email management, and data sharing.

Connections between computers require networking hardware including modems, that connect local networks to an Internet Service Provider (ISP)161, and routers that direct data flows within and between networks, often wirelessly.

FIGURE 12.6: Conceptualization of internet information transfer. Figure uses vector art from https://www.flaticon.com (Md Tanvirul Haque), https://www.onlinewebfonts.com (licensed by CC BY 4.0 Amila Ruwan) and https://www.vecteezy.com.

Data transfer follows arrows in the Fig 12.6 under a formal procedure called packet switching. In packet switching data units called packets –underlain by data bits– are generated and transmitted. A packet consists of a header (that contains handling information and the packet destination) and a payload (the transferred information). A single data stream may require multiple independent packets which must be reassembled when a data transfer is completed. The overall approach allows information subsets to be re-routed, preventing transfer roadblocks.

12.9.1.1 Protocols

Particular protocols are required for internet communications that specify how data are packetized, addressed, transmitted and received. These procedures are required for all internet and software and hardware, allowing internet communications to work in the same way regardless of operating systems and other constraints. The internet protocol suite includes the following.

-

Internet Protocol (IP): The internet address system (IP address) that directs data packets to particular network locations. We can distinguish a public IP address (one assigned by your ISP to your router for internet access) and a private IP address (which is assigned by your router and used in your local network). A public IP locates your device from the perspective of the rest of the internet (Fig 12.7). IP addresses, both public and private, are currently underlain by one of two numerical methods.

-

IPv4 is based on 32 bits, and thus allows \(2^{32}\) distinguishable addresses. Address codes are generally displayed as four, eight bit numbers (decimal numbers from 0-255), separated by decimal symbols, or dashes. For example:

134.50.65.454. -

IPv6 is based on 128 bits, and thus allows approximately \(3.403 \times 10^{38}\) distinguishable addresses. Address codes are based on up to eight hexadecimal representations, separated by colons, e.g.,

5649:ca30:a26b:2eba.

-

IPv4 is based on 32 bits, and thus allows \(2^{32}\) distinguishable addresses. Address codes are generally displayed as four, eight bit numbers (decimal numbers from 0-255), separated by decimal symbols, or dashes. For example:

FIGURE 12.7: Conceptualization of public and private IP addresses. Figure uses vector art from https://www.vecteezy.com.

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): Breaks data into standardized packets (and headers), and error-checks and reassembles packets sent in a data stream.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP): Provides rules for web content that provide a foundation for the world wide web (a collection of resources connected by hyperlinks). The protocol operates on a client-server basis, with client’s making making requests for server tasks (Fig 12.6). HTTPS, a “secure” version of HTTP, is used by more than 85% of websites.

-

Secure Shell Protocol (SSH): A protocol for operating network services securely over an unsecured network. The SSH can be called from Unix-like shells (e.g., BASH), as well as cmd and PowerShell using the command

ssh.

12.9.2 The Web

The world wide web (or simply web) allows internet access to media through dedicated web servers162, under the rules of HTTP or HTTPS. Websites are accessed by specifying a unique Uniform Resource Locator (URL) in a web browser program (e.g. Mozilla\(^{\circledR}\) Firefox, Apple\(^{\circledR}\) Safari). A URL will contain both a domain name, e.g., amalgamofr.org (amalgamofr and .org are considered second-level and top-level domain locations, respectively), along with the protocol (e.g.,https://), and, possibly, a path. The complete URL for the Ch 12 path in this book is: https://amalgamofr.org/ch12.

Domain names exist because they are easier to remember than IP addresses. However, they must be translated to binary, machine-readable IP addresses to allow communication between users and servers. This process is managed by Domain Name System (DNS) servers containing a copy of the master DNS database (slave DNS zone), which is updated many times a day.

Example 12.11 \(\text{}\)

To get private IP information about my personal (Windows) computer I can use the command ipconfig in cmd.

Windows IP Configuration

Ethernet adapter Ethernet:

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . : isu.edu

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::93b7:ac3e:2b2e:4022%17

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 134.50.65.234

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.255.0

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . : 134.50.65.254

Ethernet adapter Ethernet 2:

Media State . . . . . . . . . . . : Media disconnected

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . :

Ethernet adapter vEthernet (WSL (Hyper-V firewall)):

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . :

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::5649:ca30:a26b:2eba%19

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 172.27.160.1

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.240.0

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . : There are three potential private network connections on my machine, two of which are being used. The first, with IPv4 Address 134.50.65.234 allows connectivity to my Idaho State University network account. The second, allows connectivity to the The Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) running on my machine.

Locating a public (internet-facing) IP address requires use of external services. In the code below,I use the cmd command nslookup to access the website myip.opendns.com and the service resolver1.opendns, provided by OpenDNS (which is managed by Cisco)

The output 929.77.199.293 below is my (altered) public IP address (it is generally not a good idea to share your public IP address).

Non-authoritative answer:

Server: dns.sse.cisco.com

Address: 929.77.199.293

Name: myip.opendns.com

Address: 134.50.65.234\(\blacksquare\)

The BASH tool curlallows one to transfer data to or from a server using URLs. Variants of curl also exist for cmd and PowerShell.

Example 12.12 \(\text{}\)

Here I download the simple mothur dataset from Example 9.14 using its URL, and redirect the data to the current working directory.

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0100 551 100 551 0 0 4112 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 4304\(\blacksquare\)

One can also use R functions, including download.file() and read.table() (if data are tabular), for internet downloads.

Example 12.13 \(\text{}\)

Here I download taxon.txt and redirect it to my working directory as the file taxon2.txt.

download.file("https://amalgamofr.org/taxon.txt", "taxon2.txt")\(\blacksquare\)

Example 12.14 \(\text{}\)

I am an administrator for a server that contains a number of websites, including several that host Shiny apps (see Section 11.5.7.2). Below I gain access to the server using ssh.

> ssh [email protected]

[email protected]'s password:The server is a remote Linux computer with a 64 bit x86 CPU:

the IP address of the server is 172-31-35-117. The IPv4 range 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255 is reserved for private networks, and commonly used by AWS.

\(\blacksquare\)

12.10 Optimizing R

Because attention was given to computational efficiency in several earlier sections in this chapter, here I briefly consider several methods for optimizing R. In particular, I consider the use of R-interfaces, including scripting from command line OS shells to implement high performance computers (HPCs) and parallel computing.

Exercises

Compare x86 and ARM processor architectures.

What is the value of \(\beta\) in Eq (12.1) for binary and decimal systems?

Identify the the CPU processor architecture and operating system of your computer using R.

-

Define the following terms:

- Motherboard

- Central processing unit (CPU)

- Random access memory (RAM)

- Primary memory

- Secondary memory

- Volatile memory

- Non-volatile memory

How many bits are in 5 gigabytes? How many are in 6 gibibytes?

What is the level of trustworthy precision (in number of digits) for decimal fractional components in R (and all software that uses 64 bit double precision)?

Obtain the five bit binary sequence for the number 21, by hand. Check your answer using

dec2bin().Find the decimal number corresponding to the five bit binary sequence

11111, by hand. Check your answer usingbin2dec().Find the 64 bit expression for the decimal number \(-2\) (minus 2) using the function

bit64(), as shown in Example 12.7. Back-transform this binary representation to the decimal number by hand using Eq. (12.2). Use R functions likestrsplit()unlist(), etc.What does

310 =112 =216 mean?What is the decimal representation of the hexadecimal code

B0? Why?What is the hexadecimal code for the Unicode character

<? Why?How would we code for the Unicode character

<in R?Distinguish an IP address, a URL, and a domain name.

What is the HTTP and SSH?